2 Corinthians 8:16-9:5 – Blessing Rather Than Extortion

[This is copied from my book Searching for the Pattern, pp. 90-104. Due to a recent bout with COVID-19, I have not had the energy or time to do any original writing on 2 Corinthians 8-9. However, I think the following captures the essence of Paul’s theological interests in this section of the letter. One more video will cover the rest of chapter 9 next week.]

2 Corinthians 8-9 – What Paul Doesn’t Do

Here’s how my continued investigation played out, at least in part.

I have heard it said that the Bible is its own best interpreter. There is much truth in that. Since the Bible offers a coherent account of God’s scheme of redemption, one part illuminates another part.

This is particularly true when we are reading the same human author, like Paul. What Paul writes in Colossians will helpfully illuminate what Paul means in Ephesians. This is more pronounced when Paul is writing to the same church about the same thing. Consequently, if we want to understand what lies in the background of Paul’s instructions in 1 Corinthians 16, it is helpful to hear how Paul grounds and explains this collection in 2 Corinthians 8-9.

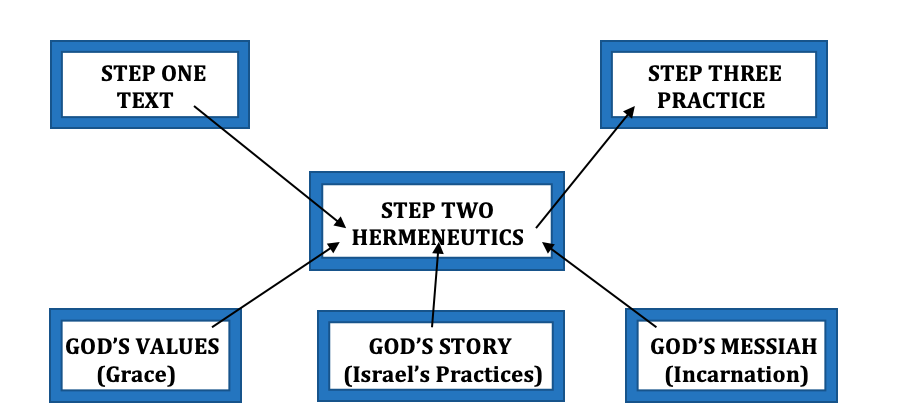

As we read 2 Corinthians 8-9 where Paul encourages the Corinthians to follow through on their commitment to help the saints in Jerusalem, we see the inner workings of Paul’s understanding as he provides a rationale for their giving. We see, in effect, Paul’s own hermeneutic (or step two) at work. We see how Paul gets from (1) there are needy saints in Jerusalem to (3) you Corinthians ought to supply their needs. What is the second step that demands the move from (1) to (3)?

Interestingly, in this text Paul does not seem to inhabit the same patternistic world in which I grew up, at least not the sort of pattern for which I searched. First, he does not command the Corinthians to give. “I am not commanding you,” Paul wrote (2 Corinthians 8:8).

Second, he does not demand they obey the pattern I thought was in 1 Corinthians 16:1-2. Paul does not remind them of what he had previously prescribed as if their first day of the week giving was part of their faithfulness to a pattern. He neither details a pattern nor itemizes the blueprint particulars that constitute what a faithful church practices regarding giving. He neither specifies the laws that govern this act of worship nor reminds them of the dire consequences of neglecting it.

Third, he does not draw a line of fellowship concerning the collection. Paul does not make this collection—for which he gave directions in 1 Corinthians 16:1-2—a matter of fellowship or communion with him. Their non-participation would be an embarrassment and a lack of grace on their part, but it would not violate whatever pattern is embedded in 1 Corinthians 16:1-2 as a test of fellowship.

In other words, Paul does not do what the method I had learned would have done and what I have heard done over the years practically every Sunday. Paul does not say, “you are commanded to give every first day of the week, and if you don’t, you are unfaithful to the pattern God established.” I often used Paul’s direction for the collection in 1 Corinthians 16:1-2 to establish pattern authority for why faithful churches share their financial resources every first day of the week. I regarded it, as many had before me, as part of an exclusive pattern of worship. It was one of the five acts of worship without which the Sunday assembly is incomplete and could not be considered a community who worshipped in spirit and in truth (John 4:24).

Paul does not use that sort of pattern authority. He does not remind them of what I supposed was a pattern command in 1 Corinthians 16. He does not prescribe giving as a matter of obedience to a pattern of congregational worship.

What does Paul do? How does Paul call a wealthy Gentile congregation in Greece to contribute to a collection for poor Jewish saints in Jerusalem?

There is only one imperative in the text: “finish the work” (2 Corinthians 8:11). The Corinthians had promised to give to the needy in Jerusalem, and Paul expects them to keep their promise. They had expressed a prior willingness, even eagerness, to contribute (2 Corinthians 8:10-12). Though he does not command them, he does offer a rationale to motivate them to act on their prior willingness according to their ability.

Ultimately, Paul does not use a two-step rationale such as: “This is the pattern God demands; therefore, do it.” Neither does he introduce the sort of rationales that establish a pattern for the church based on detailed prescribed practices as might be expected. Rather, he calls the Corinthians to embody and practice a different sort of pattern.

As I understand Paul in these two chapters, I see three (perhaps more) overlapping and mutually enriching organizing emphases. Together, these point to a pattern which grounds Paul’s invitation to the Corinthians to participate in the grace of giving.

A Key Principle in 2 Corinthians 8-9

One of the most significant words in 2 Corinthians 8-9, if not the most significant, is the Greek word charis, which means grace. Its ten occurrences in these two chapters are the highest concentration in the New Testament.

- the grace (charis) of God given to the churches of Macedonia (8:1)

- the privilege (charis) of sharing in this ministry to the saints (8:4)

- complete this generous (charis) undertaking among you (8:6)

- as you excel in everything…excel also in this generous (charis) undertaking (8:7)

- for you know the generous (charis) act of our Lord Jesus Christ (8:9)

- Thanks (charis) be to God (8:16)

- while administering this generous (charis) undertaking (8:19)

- God is able to provide you with every blessing (charis) in abundance (9:8)

- the surpassing grace (charis) God…has given you (9:14).

- Thanks (charis) be to God for his indescribable gift (9:15).

These statements provide several different angles on the grace of God. God gives grace (2 Corinthians 8:1, 9; 9:8, 14), the Corinthians administer the grace of God in their ministry to others (2 Corinthians 8:4, 6, 7, 17), and all, including those who receive this ministry, give grace (thanks) to God (2 Corinthians 8:16; 9:15).

While the profound depth of these statements is inexhaustible, my purpose is to highlight one point. Fundamentally, Paul roots his invitation to participate in the collection for the Jerusalem saints in God’s grace. He reminds them that (1) God has graced them, (2) they are the instruments of God’s grace to the poor, and (3) their ministry will result in grace (thanksgiving) to God as well as God’s glory (2 Corinthians 9:13). God’s own grace, whether in creation, providence, or redemption, should move the Corinthians to act graciously. They should “finish the task” because they are graced people through whom God graces others with the result that they will grace God.

We might call the function of grace in Paul’s persuasive speech a form of “principlizing,” though it has more substance than a kind of moralizing. As we read Paul’s passionate plea, he uses the principle of grace in its many manifestations to articulate a vision for the heart of God and how the Corinthians might participate in that heart.

Why give to the poor? Whether local or distant, whether Jew or Gentile, whether known or unknown, Paul roots this gift in God’s grace. We give because we are the recipients of God’s grace, empowered by that grace, and moved by the goal of gracing God (thanks and glory).

Paul does not ground his call to share grace in a command or a pattern of church practices. Rather, he grounds it in God’s own gracious giving. We give because God has given to us, and we give because we want to be like God. We respond to God’s grace by doing what God does. Grace is no static command but an internal dynamic at work in the scheme of redemption and in our lives so that we might imitate and glorify God.

Paul, then, uses a principle profoundly grounded in God’s own identity and actions in order to call the Corinthians to fully live out the grace they have received. Let us imitate Paul’s hermeneutical move ourselves. If God’s grace is the ground of giving to the poor, this grace is not limited only to saints. 1 Corinthians 16:1-2 cannot mean that church funds are only for church people because God’s grace is for all people and the grace of God has appeared to all people (Titus 2:11).

I remember, and still sometimes hear, the language that sometimes introduces the offering. “We are commanded to give every first day of the week.” But I also have heard the language from 2 Corinthians 9, “God loves a cheerful giver.” Paul did not do the former in 2 Corinthians 8-9 (command every congregation to take up a collection every first day of the week) but the latter. Paul did not command or expect conformity to a blueprint, but called the Corinthians to conform to the gospel of Jesus Christ. If we gratefully receive God’s grace, we will then cheerfully share it. This was Paul’s approach in 2 Corinthians 8-9.

2 Corinthians 8-9 – Paul’s Use of Scripture

If Paul does not appeal to a prescribed pattern of church practices as the ground of the collection, does Paul appeal to Scripture at all? When Paul wants to persuade people to give to the poor, what role does Scripture play?

What was Scripture for Paul? In 55-56 A.D. we would not expect him to appeal to any New Testament documents except those he had already written (1 & 2 Thessalonians, for example). Nevertheless, for Paul, all Scripture is “inspired and profitable for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness,” and it is sufficient to equip believers “for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16-17). These were the “sacred writings” Timothy had known from childhood, and they were able to instruct him “for salvation through faith in Jesus Christ” (2 Timothy 3:15). This Scripture is what we have called the Old Testament, and it has the capacity to instruct us, correct us, guide us, and equip us for “every good work,” including giving to the poor. Paul identifies the grace of giving as a “good work” in 2 Corinthians 9:8.

In 2 Corinthians 8-9, Paul appeals to the Hebrew Bible at least three times. First, God’s gift of manna in the wilderness teaches the principle of a fair balance. The needy are supplied out of the abundance of the wealthy so that everyone has what they need. Paul quotes Exodus 16:18 in 2 Corinthians 8:15 as an example that grounds Paul’s call for shared resources so that there is equity within the body of Christ. God supplies manna (resources) for the sake of the community, and the community shares them so that all needs are met. The instruction to gather what one needs arises out of the divine intent that one person not have too much and another person not have too little. The way God supplied the needs of Israel is a model for how we supply each other’s needs. What moves God should move us, that is, a grace that meets the needs of people. God is our model, and we see God’s intent through the practices of Israel.

Second, Paul quotes Psalm 112:9 in 2 Corinthians 9:9. Psalm 112 blesses the righteous person. At the same time, Psalm 111 praises God’s own identity. The righteous person of Psalm 112 is the one who imitates the God who is described in Psalm 111. Psalm 112 mirrors Psalm 111. In this way, the root idea is doing what God does or becoming like God in our lives and practices. Just as God is generous, so the righteous person shares generously with the poor. God, in fact, supplies the seed or wealth which we, in imitation of God, scatter among the poor. Interestingly, 2 Corinthians 9:8 tells us that God supplies us for “every good work,” and then Paul uses Psalm 112 to identify that “good work,” which is scattering God’s gifts to us among the poor. In this way, Paul appeals to Scripture (Psalm 112) to equip them for this good work of sharing with the poor in Jerusalem. Thus, Psalm 112 authorizes his call for the Corinthians to participate in this good work.

Third, Deuteronomy 15 lurks in the background as well. Just as God had blessed Israel so that there should be no needy among them, the Corinthians should give generously without a grudging heart (Deuteronomy 15:10; 2 Corinthians 9:7). Paul uses the language of Deuteronomy 15. Just like Israel, God intends the church to be a place where there are no needy, and Paul invites the Corinthians to participate in the practices of Israel by continuing that intent in the present.

Paul also draws on the model of the Macedonian disciples in order to convict the Corinthians and wants the Corinthians to be an example to others (2 Corinthians 8:1-2, 24). The ongoing history of God among the Macedonians teaches the Corinthians too. Redemptive history is filled with good examples and good practices that imitate God’s own grace, and because they are grounded in God’s acts and grace, we imitate God when we share generously with others.

In the light of how the church continues the life of Israel, it is important to note that Israel’s generosity included aliens or foreigners living among them. Israel’s attitude toward aliens was rooted in God’s own love for Israel when they were aliens. Leviticus 19:34 says, “you shall love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.” In fact, needy aliens received shares of the third-year tithe (Deuteronomy 26:12-13). Moreover, the God of Israel “executes justice” for and “loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing” (Deuteronomy 10:17-18).

If the God of Israel loved the alien, provided food and clothing for the alien, and required Israel to share with the alien, then the “saints only doctrine” is inconsistent with this trajectory within the scheme of redemption. Should one say, “well, that is in the Old Testament, and we draw our church practices from Acts and the Epistles,” it is important to recognize how Paul models something different. Paul has no problem looking to Israel’s Scripture to ground the collection for the poor saints in Jerusalem in both the identity of God and the practices of Israel as God’s people. Since God’s gift (grace) of manna to Israel can teach the church about generosity toward the poor (2 Corinthians 8:13-15), then God’s treatment of the aliens within Israel can teach us about God’s generosity toward aliens today. God loves the alien today, just as God loved the alien in ancient Israel.

2 Corinthians 8-9 – Paul Appeals to Jesus

In order to ground his appeal to the Corinthians to finish the task, Paul employed (1) the theological principle of grace and (2) used Israel’s Scripture as a way to understand God’s own identity and call. In his final sentence, Paul (3) appeals to the foundational act of God in Jesus the Messiah. “Thanks be to God,” Paul writes, for God’s “indescribable gift!” (2 Corinthians 9:15). The gift, of course, is God’s Messiah, Jesus, the Son of God.

Earlier, in 2 Corinthians 8:8-9, Paul noted that the Corinthian response to this collection would test their integrity and the sincerity of their love. In effect, he wants to know if they really believe the Faith they confess. Paul does not command the Corinthians. Since Jesus himself acted out of grace rather than obligation, Paul wants the Corinthians to do the same. He wants them to imitate Jesus.

“You know,” Paul wrote, “the generous act (charis) of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The grace of Jesus is his incarnation, that is, the Word of God became flesh. Or, as Paul described it, “though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor.” The incarnation is Paul’s paradigm, and this is God’s indescribable gift. This is the pattern. God’s self-giving in the incarnation of Jesus is the model or pattern for Christian life and practice.

When we remember that the Word of God became human for the whole world and died for all people, there is no basis for the “saint’s only doctrine” in the scheme of redemption. If the incarnation of the Word of God is Paul’s rationale for sharing with the poor, and the incarnation is an expression of God’s love for the whole world, then the imitation of the incarnation in giving to the poor includes all the poor and not only the saints.

A Theological Hermeneutic?

In summary, as Paul asks the Corinthians to “finish the task,” he grounds his appeal in God’s multi-faceted grace, the practices of Israel that bear witness to God’s own life, and the incarnation of the Word of God. In essence, Paul asks the Corinthians to imitate God. This is the basis of Paul’s mission for the poor saints in Jerusalem. At every point, Paul’s method roots that mission in the identity, grace, and love of God. And, as we know from the scheme of redemption, God loves the whole world and the Messiah died for all people. Therefore, the body of Christ shares with everyone, and this grace is not limited to saints only.

Perhaps another way to say this is to recognize that Paul’s step two does not find its pattern in some detailed and exclusive blueprint for church practices but in the pattern of God’s mighty acts in Israel and Jesus the Messiah. Instead of applying a blueprint for church practices to Corinth as if he were shown an ideal pattern for how churches must conduct their Sunday assembly, Paul resources the workings of God’s grace in providence and salvation, Israel’s history, and the gospel of Jesus the Messiah. The pattern is the activity of God, which finds its fullness in the incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and exaltation of Jesus the Messiah.

What Paul is doing is what some call a “theological” interpretation. Don’t let that word intimidate you. The Greek word theos means God. Theology is the study of God, and to say something is “theological” means it is a reflection on God or about God. In particular, this approach focuses on the identity of God and how believers might imitate God. In other words, we look to who God is and what God has done in order to know what is required of us or how we might participate in God’s mission.

Another way of saying this is that we do not look for a prescribed, detailed blueprint in what the early church did as much as a theological (God-centered) pattern as to how the early church imitated God, including imitating Jesus. In other words, how did the early church embody the life of God (the theological pattern) in their own community and mission?

Paul fulfilled his commitment to the “pillars” of the church in Jerusalem to “remember the poor” (Galatians 2:9-10). He asked the churches of Galatia and Achaia, but not Macedonia, to set up an arrangement to collect money every first day of week so that when he arrived there would be no need to take up a collection. When Corinth hesitated, Paul employed his apostolic authority by way of a theological appeal rather than by way of a positive command based on a blueprint. Paul did not demand conformity to a prescribed pattern of weekly giving but invited them to imitate God and share the grace with which God had graced them for the sake of gracing God.

This does not mean, of course, that churches should give up weekly giving as part of their assemblies. In the language of the received method, it is at least a good example even though it is not an approved (binding) example. There are good reasons to give every week or to regularly share our resources with the community of faith, and those reasons are rooted in God’s grace, God’s story, and God’s Messiah. The convenient practice of weekly giving within the assembly is a healthy practice that provides the community with an opportunity to participate in the mission of God as a community, to share in this corporate moment of grateful worship, to remember that God has graced them, and to imitate God by gracing others in order that God might be graced by all.

There are many reasons to participate in God’s mission through sharing our resources. We could begin with the story of Abraham’s tithing and continue with Israel’s tithing practices. We could point to the teachings of Jesus on giving as well as the practice of the early Jerusalem church in Acts 2, 4, and 6. If we expanded the conversation to include these factors, that would employ a fuller theological hermeneutic (which enriches our understanding and motivates our sharing). But those larger resources do not entail that there is a prescribed blueprint. Communal sharing on the first day of the week conveniently continues the practice of the people of God seen throughout Scripture, but it is not a requirement mandated by a specifically prescribed pattern for the church.